Deadlines are seductive, and it’s easy to see why: the idea that something will be completed by a certain date helps us add a sense of order to our lives. It’s no wonder the theme of the recent Conservative Party Conference that’s just wrapped up in Manchester was “Get Brexit Done.” It’s a simple message with a simple clean subtext: finish task A, so we can move on to tasks B, C, D and – time permitting – E.

Of course, anybody following the detail knows Brexit is anything but simple, and the idea that it can be all neatly wrapped up by 31 October is for the birds. And while it’s less of a leap into the unknown than disentangling a nation from 46 years of economic union, the same is actually true for digital deadlines. While seeming to offer firm direction and leadership, absolute deadlines can end up hurting your website in both the short and long term.

Arbitrary and unhelpful

First off, let’s look at how and why deadlines are formed. They’re usually set from the top – possibly by management or funding body – and the farther you are away from a problem, the more tricky detail becomes fuzzy: it’s all too easy to set a fixed deadline when you don’t have to confront the day-to-day contradictions yourself.

As a result, the truth is that these deadlines are often entirely arbitrary. Launching a website ‘by the end of November’, say, has a certain neat appeal to it. But given weeks and months are human constructs anyway, would it really hurt to give something a little longer to be the best it can be?

The answer is almost always no, but making that case can be tricky. It’s certainly worth trying though because deadlines kill good work. They encourage corners to be cut while inducing stress, which in turn frequently leads to mistakes. And even if you do avoid burnout in a blaze of late nights and stress, you can bet that you’ll see a productivity dip once the date has been cleared, whether or not everything is working as expected.

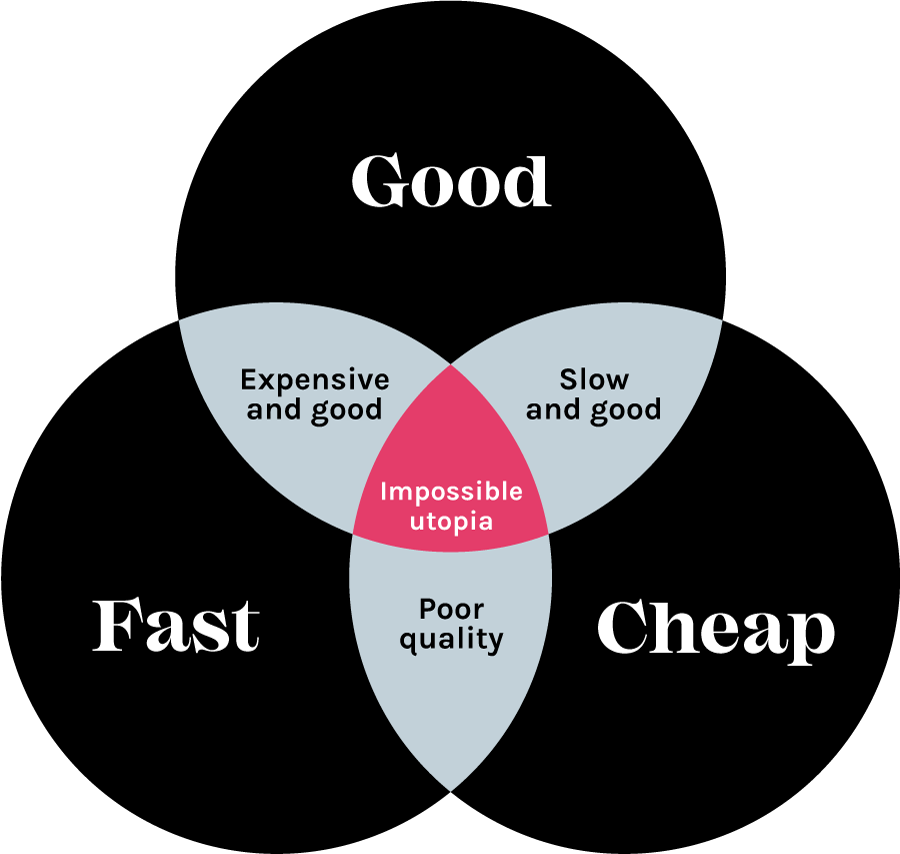

While it is possible to do good work quickly, such an approach requires money to be thrown at the problem. In the charity sector, that money isn’t always readily available, and as the old Venn diagram below illustrates, you can do good work fast at great expense or slow on the cheap. You can’t do good work fast and cheaply, no matter how many times you repeat the deadline: something has to give.

The old ‘Good, fast, cheap. Pick two’ Venn diagram still holds true. And when charity budgets are tight, longer timelines are the only way to ensure good quality work.

But worse than that, a hard deadline on building a website is a sign that management is seeing the project as done and dusted, when the best companies understand that these things should be iterative. Leaving aside for one moment the fact that it’s a very good idea to budget for ongoing maintenance, things often don’t perform quite as you’d like the first time. Closing the door on a project with an absolute deadline prevents you from adapting and improving: it’s the very opposite of Silicon Valley’s “fail fast” mantra. And yes, there are certainly problems with that idea when taken to extremes, but if you’re a charity with a small budget then learning to fail quickly and adapt is pretty much essential. You just don’t have the money to waste.

Slow and steady wins the race

Which brings us to another point on a similar note: experienced digital agencies including Fat Beehive tend to work in sprints and phases, rather than building websites in one go. The reasons for this are manyfold, but the gist is this: breaking down a big project into segments is easier on developers and means you can concentrate on the things that are really important, without being distracted by “nice to have” features.

The aim is to get a minimum viable product (MVP) out as quickly as possible, test it and then build from there, advancing what’s working and stepping back from things that aren’t, in a data-driven fashion. After all, it’s better to get the basics right and do a small number of things well than to launch quickly with a whole bunch of poorly implemented or untested bloat.

While this approach can work with a series of mini-deadlines, one single monster deadline isn’t helpful, because it rushes you through testing and analysis – the same testing and analysis that will ultimately make or break the project.

“While this approach can work with a series of mini-deadlines, one single monster deadline isn’t helpful, because it rushes you through testing and analysis – the same testing and analysis that will ultimately make or break the project.”

It’s understandable why people at the top might be distrusting of this approach: it looks like an excuse to buy time, or for an unscrupulous agency to try and string more cash than necessary out of a client, but the results speak for themselves. The key thing here is to trust your agency, which has been through the process hundreds of times before and has the experience to prioritise and respond quickly to what the data reveals.

To be clear, deadlines have their place and there can be very good reasons for them. The problem is when they’re arbitrary, inflexible and seen as the finale of a product, rather than the end of a first phase. Convincing management to be more flexible with these things can seem like an impossible task but, ultimately, if no attempt is made then you could well be setting your website up to fail before the first line of code has even been laid down.